3.3 Clock Quality

Last update: June 27, 2022 16:22 UTC (1a7aee0a0)

3.3.1 Frequency Error

3.3.1.1 How bad is a Frequency Error of 500 PPM?

3.3.1.2 What is the Frequency Error of a good Clock?

When discussing clocks, the following quality factors are helpful:

-

The smallest possible increase of time the clock model allows is called resolution. If a clock increments its value once per second, the resolution is one second.

-

A high resolution does not help if you can’t read the clock. Therefore the smallest possible increase of time that can be experienced by a program is called precision.

In NTP precision is determined automatically, and is measured as a power of two. For example when ntpq -c rl prints precision=-16, the precision is about 15 microseconds (2^-16 s).

If you like formal definitions, consider this one: “Precision is the random uncertainty of a measured value, expressed by the standard deviation or by a multiple of the standard deviation.”

-

When repeatedly reading the time, the difference may vary almost randomly. The difference of these differences (second derivation) is called jitter.

-

A clock not only needs to be read, it must be set. The accuracy determines how close the clock is to an official time reference like UTC.

Again, if you prefer a formal definition: “Accuracy is the closeness of the agreement between the result of a measurement and a true value of the measurand.”

-

Unfortunately, common clock hardware is not very accurate. This is because the frequency that makes time increase is never exactly right. Even an error of only 0.001% would make a clock be off by almost one second per day. This is why discussing clock problems uses very fine measures: One PPM (Part Per Million) is 0.0001% (1E-6).

Real clocks have a frequency error of several PPM quite frequently. Some of the best clocks available still have errors of about 1E-8 PPM. For example, one of the clocks that is behind the German DCF77 has a stability of 1.5 ns/day (1.7E-8 PPM)

-

Even if the systematic error of a clock model is known, the clock will never be perfect. This is because the frequency varies over time, mostly influenced by temperature, but it could be due to other factors such as air pressure or magnetic fields. Reliability determines how long a clock can keep time within a specified accuracy.

-

For long-term observation one may also notice variations in the clock frequency. The difference of the frequency is called wander. Therefore there can be clocks with poor short-term stability, but with good long-term stability, and vice versa.

3.3.1 Frequency Error

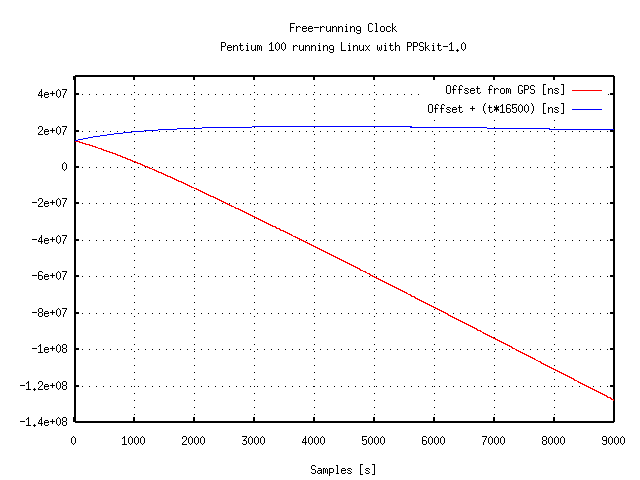

It’s not sufficient to correct the clock once. Figure 3.3a illustrates the problem. The offset of a precision reference pulse has been measured with the free-running system clock. The figure shows that the system clock gains about 50 milliseconds per hour (red line). Even if the frequency error is taken into account, the error spans a few milliseconds within a few hours (blue line).

Figure 3.3a: Offset for a free-running Clock

Even if the offset seems to drift in a linear way, a closer examination reveals that the drift is not linear.

Example 3.3a: Quartz Oscillators in IBM compatible PCs

In my experiments with PCs running Linux I found out that the frequency of the oscillator’s correction value increases by about 11 PPM after powering up the system. This is quite likely due to the increase of temperature. A typical quartz is expected to drift about 1 PPM per °C.

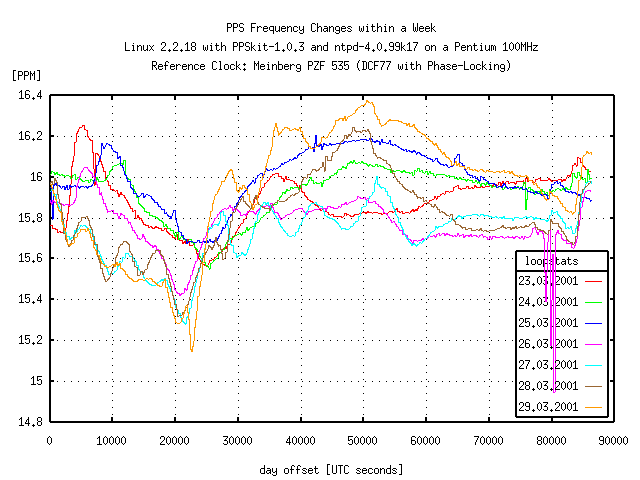

Even for a system that has been running for several days in a non-air-conditioned office, the correction value changed by more than 1 PPM within a week (see Figure 3.3b for a snapshot from that machine). It is possible that a change in supply voltage also changes the drift value of the quartz.

As a consequence, without continuous adjustments the clock must be expected to drift away at roughly one second per day in the worst case. Even worse, the values quoted above may increase significantly for other circuits, or even more for extreme environmental conditions.

Figure 3.3b: Frequency Correction within a Week

Some spikes may be due to the fact that the DCF77 signal failed several times during the observation, causing the receiver to resynchronize with an unknown phase.

3.3.1.1 How bad is a Frequency Error of 500 PPM?

As most people have some trouble with that abstract PPM (parts per million, 0.0001%), I’ll simply state that 12 PPM correspond to one second per day roughly. So 500 PPM means the clock is off by about 43 seconds per day. Only poor old mechanical wristwatches are worse.

3.3.1.2 What is the Frequency Error of a good Clock?

I’m not sure, but but I think a chronometer is allowed to drift mostly by six seconds a day when the temperature doesn’t change by more than 15° Celsius from room temperature. That corresponds to a frequency error of 69 PPM.

I read about a temperature compensated quartz that should guarantee a clock error of less than 15 seconds per year, but I think they were actually talking about the frequency variation instead of absolute frequency error. In any case that would be 0.47 PPM. As I actually own a wrist watch that should include that quartz, I can state that the absolute frequency error is about 2.78 PPM, or 6 seconds in 25 days.

For the Meinberg GPS 167 the frequency error of the free running oven-controlled quartz is specified as 0.5 PPM after one year, or 43 milliseconds per day (roughly 16 seconds per year). See the examples in Mills-speak.