5. How does it work?

Last update: June 27, 2022 16:22 UTC (1a7aee0a0)

This section will try to explain how NTP will construct and maintain a working time synchronization network.

5.1 Basic Concepts

To help understand the details of planning, configuring, and maintaining NTP, some basic concepts are presented here. The focus in this section is on theory.

5.1.1 Time References

5.1.1.1 What is a reference clock?

5.1.1.2 How will NTP use a reference clock?

5.1.1.3 How will NTP know about Time Sources?

5.1.1.4 What happens if the Reference Time changes?

5.1.1.5 What is a stratum 1 Server?

5.1.2 Time Exchange

5.1.2.1 How is Time synchronized?

5.1.2.2 Which Network Protocols are used by NTP?

5.1.2.3 How is Time encoded in NTP?

5.1.2.4 When are the Servers polled?

5.1.3 Performance

5.1.3.1 How accurate will my Clock be?

5.1.3.2 How frequently will the System Clock be updated?

5.1.3.3 How frequently are Correction Values updated?

5.1.3.4 What is the Limit for the Number of Clients?

5.1.4 Robustness

5.1.4.1 What is the stratum?

5.1.4.2 How are Synchronization Loops avoided?

5.1.5 Tuning

5.1.5.1 What is the allowed range for minpoll and maxpoll?

5.1.5.2 What is the best polling Interval?

5.1.6 Operating System Clock Interface

5.1.6.1 How will NTP discipline my Clock?

5.1.1 Time References

5.1.1.1 What is a reference clock?

A reference clock is some device or machinery that spits out the current time. The special thing about these things is accuracy: reference clocks must accurately follow some time standard.

Typical candidates for reference clocks are very expensive cesium clocks. Cheaper, and thus more popular, clocks are receivers for some time signals broadcasted by national standard agencies. A typical example would be a GPS (Global Positioning System) receiver that gets the time from satellites. These satellites in turn have a cesium clock that is periodically corrected to provide maximum accuracy.

Less expensive (and accurate) reference clocks use one of the terrestrial broadcasts known as DCF77, MSF, and WWV.

In NTP these time references are named stratum 0, the highest possible quality. Each system that has its time synchronized to some reference clock can also be a time reference for other systems, but the stratum will increase for each synchronization.

5.1.1.2 How will NTP use a reference clock?

A reference clock will provide the current time. NTP will compute some additional statistical values that describe the quality of time it sees. Among these values are: offset (or phase), jitter (or dispersion), frequency error, and stability. Each NTP server maintains an estimate of the quality of its reference clocks and of itself.

5.1.1.3 How will NTP know about Time Sources?

There are serveral ways an NTP client knows which NTP servers to use:

- Servers to be polled can be configured manually.

- Servers can send the time directly to a peer.

- Servers may send out the time using multicast or broadcast addresses.

5.1.1.4 What happens if the Reference Time changes?

Ideally the reference time is the same everywhere in the world. Once synchronized, there should not be any unexpected changes between the clock of the operating system and the reference clock. Therefore, NTP has no special methods to handle the situation.

Instead, ntpd’s reaction will depend on the offset between the local clock and the reference time. For a tiny offset ntpd will adjust the local clock as usual; for small and larger offsets, ntpd will reject the reference time for a while. In the latter case the operation system’s clock will continue with the last corrections effective while the new reference time is being rejected. After some time, small offsets (significantly less than a second) will be slewed (adjusted slowly), while larger offsets will cause the clock to be stepped (set anew). Huge offsets are rejected, and ntpd will terminate itself, believing something very strange must have happened.

This algorithm is also applied when ntpd is started for the first time or after reboot.

5.1.1.5 What is a stratum 1 Server?

A server operating at stratum 1 belongs to the class of best NTP servers available, because it has a reference clock attached to it. As accurate reference clocks are expensive, only a few of these servers are publicly available.

In addition to having a precise and well-maintained and calibrated reference clock, a stratum 1 server should be highly available as other systems may rely on its time service. Maybe that’s the reason why not every NTP server with a reference clock is publicly available.

5.1.2 Time Exchange

5.1.2.1 How is Time synchronized?

Time can be passed from one time source to another, typically starting from a reference clock connected to a stratum 1 server. Servers synchronized to a stratum 1 server will be stratum 2. Generally the stratum of a server will be one more than the stratum of its reference.

Synchronizing a client to a network server consists of several packet exchanges where each exchange is a request and reply pair. When sending out a request, the client inserts its own time (originate timestamp) into the packet being sent. When a server receives the packet, it inserts its own time (receive timestamp) into the packet, and the packet is returned after putting a transmit timestamp into the packet. When receiving the reply, the receiver will once more log its own receipt time to estimate the travelling time of the packet. The travelling time (delay) is estimated to be half of “the total delay minus remote processing time”, assuming symmetrical delays.

Those time differences can be used to estimate the time offset between both machines, as well as the dispersion (maximum offset error). The shorter and more symmetric the round-trip time, the more accurate the estimate of the current time.

Time is not believed until several packet exchanges have taken place, each passing a set of sanity checks. Only if the replies from a server satisfy the conditions defined in the protocol specification, is the server considered valid. Time cannot be synchronized from a server that is considered invalid by the protocol. Some essential values are put into multi-stage filters for statistical purposes to improve and estimate the quality of the samples from each server. All used servers are evaluated for a consistent time. In case of disagreements, the largest set of agreeing servers (truechimers) is used to produce a combined reference time, thereby declaring other servers as invalid (falsetickers).

Usually it takes about five minutes (five good samples) until a NTP server is accepted as a synchronization source. Interestingly, this is also true for local reference clocks that have no delay at all by definition.

After initial synchronization, the quality estimate of the client usually improves over time. As a client becomes more accurate, one or more potential servers may be considered invalid after some time.

5.1.2.2 Which Network Protocols are used by NTP?

NTP uses UDP packets for data transfer because of the fast connection setup and response times. The official port number for NTP (that ntpd and ntpdate listen and talk to) is 123.

The reference implementation supports the NTP protocol on port 123. It does not support the Time Protocol (RFC 868) on port 37. NTP is newer and more precise than the older Time protocol.

5.1.2.3 How is Time encoded in NTP?

There was a nice answer from Don Payette in news://comp.protocols.time.ntp, slightly adapted:

The NTP timestamp is a 64 bit binary value with an implied fraction point between the two 32 bit halves. If you take all the bits as a 64 bit unsigned integer, stick it in a floating point variable with at least 64 bits of mantissa (usually double) and do a floating point divide by 2^32, you’ll get the right answer.

As an example the 64 bit binary value:

00000000000000000000000000000001 10000000000000000000000000000000

equals a decimal 1.5. The multipliers to the right of the point are 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, etc.

To get the 200 picoseconds, take a one and divide it by 2^32 (4294967296), you get 0.00000000023283064365386962890625 or about 233E-12 seconds. A picosecond is 1E-12 seconds.

In addition one should know that the epoch for NTP starts in year 1900 while the epoch in UNIX starts in 1970. Therefore the following values both correspond to 2000-08-31_18:52:30.735861

UNIX: 39aea96e.000b3a75

00111001 10101110 10101001 01101110.

00000000 00001011 00111010 01110101

NTP: bd5927ee.bc616000

10111101 01011001 00100111 11101110.

10111100 01100001 01100000 00000000

5.1.2.4 When are the Servers polled?

When polling servers, a similar algorithm as described in Q: 5.1.3.3. is used. Basically the jitter (white phase noise) should not exceed the wander (random walk frequency noise). The polling interval tries to be close to the point where the total noise is minimal, known as Allan intercept, and the interval is always a power of two. The minimum and maximum allowable exponents can be specified using minpoll and maxpoll respectively. If a local reference clock with low jitter is selected to synchronize the system clock, remote servers may be polled more frequently than without a local reference clock (after version 4.1.0) of ntpd. The intended purpose is to detect a faulty reference clock in time.

5.1.3.1 How accurate will my Clock be?

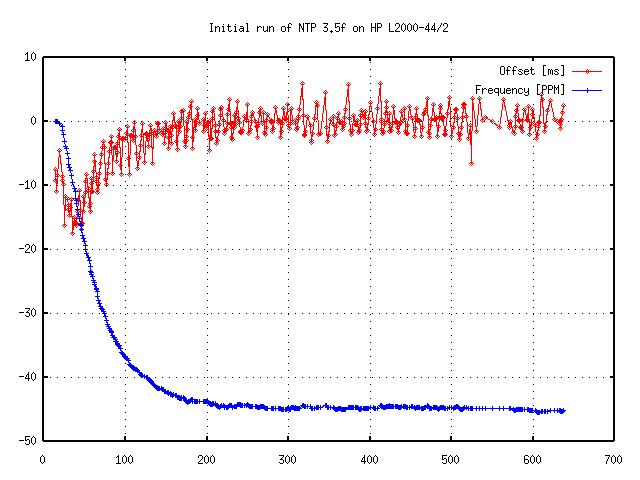

For a general discussion see Section 3. Also keep in mind that corrections are applied gradually, so it may take up to three hours until the frequency error is compensated (see Figure 5.1a).

Figure 5.1a: Initial Run of NTP

The final achievable accuracy depends on the time source being used. Basically, no client can be more accurate than its server. In addition, the quality of the network connection also influences the final accuracy. Slow and non-predictable networks with varying delays are bad for good time synchronization.

A time difference of less than 128ms between server and client is required to maintain NTP synchronization. The typical accuracy on the Internet ranges from about 5ms to 100ms, possibly varying with network delays. A survey by Professor David L. Mills suggests that 90% of the NTP servers have network delays below 100ms, and about 99% are synchronized within one second to the synchronization peer.

With PPS synchronization an accuracy of 50μs and a stability below 0.1 PPM is achievable on a Pentium PC running Linux. However, there are some hardware facts to consider. Judah Levine wrote:

In addition, the FreeBSD system I have been playing with has a clock oscillator with a temperature coefficient of about 2 PPM per degree C. This results in time dispersions on the order of lots of microseconds per hour (or lots of nanoseconds per second) due solely to the cycling of the room heating/cooling system. This is pretty good by PC standards. I have seen a lot worse.

Terje Mathisen wrote in reply to a question about the actual offsets achievable: “I found that 400 of the servers had offsets below 2ms, (…)”

David Dalton wrote about the same subject:

The true answer is: It All Depends…..

Mostly, it depends on your networking. Sure, you can get your machines within a few milliseconds of each other if they are connected to each other with Ethernet connections and not too many routers hops in between. If all the machines are on the same quiet subnet, NTP can easily keep them within one millisecond all the time. But what happens if your network get congested? What happens if you have a broadcast storm (say 1,000 broadcast packets per second) that causes your CPU to go over 100% load average just examining and discarding the broadcast packets? What happens if one of your routers loses its mind? Your local system time could drift well outside the “few milliseconds” window in situations like these.

5.1.3.2 How frequently will the System Clock be updated?

As time should be a continuous and steady stream, ntpd updates the clock in small quantities. However, to keep up with clock errors, such corrections have to be applied frequently. If adjtime() is used, ntpd will update the system clock every second. If ntp_adjtime() is available, the operating system can compensate clock errors automatically, requiring only infrequent updates. See also Section 5.2 and Q: 5.1.6.1..

5.1.3.3 How frequently are Correction Values updated?

NTP maintains an internal clock quality indicator. If the clock seems stable, updates to the correction parameters happen less frequently. If the clock seems instable, more frequent updates are scheduled. Sometimes the update interval is also termed stiffness of the PLL, because only small changes are possible for long update intervals.

There’s a decision value named poll adjust that can be queried with ntpdc’s loopinfo command. A value of -30 means to decrease the polling interval, while a value of 30 means to increase it within the bounds of minpoll and maxpoll. The value of watchdog timer is the time since the last update.

ntpdc> loopinfo

offset: -0.000102 s

frequency: 16.795 ppm

poll adjust: 6

watchdog timer: 63 s

5.1.3.4 What is the Limit for the Number of Clients?

The limit depends on several factors, like speed of the main processor and network bandwidth, but the limit is quite high. Terje Mathisen once presented a calculation:

2 packets/256 seconds * 500 K machines -> 4 K packets/second (half in each direction).

Packet size is close to minimum, definitely less than 128 bytes even with cryptographic authentication:

4 K * 128 -> 512 KB/s.

So, as long as you had a dedicated 100 Mbit/s full duplex leg from the central switch for each server, it should see average networks load of maximim 2-3%.

5.1.4 Robustness

5.1.4.1 What is the stratum?

The stratum is a measure for synchronization distance. Opposed to jitter or delay the stratum is a more static measure. Basically from the perspective of a client, it is the number of servers to a reference clock. So a reference clock itself appears at stratum 0, while the closest servers are at stratum 1. On the network there is no valid NTP message with stratum 0.

A server synchronized to a stratum n server will be running at stratum n + 1. The upper limit for stratum is 15. The purpose of stratum is to avoid synchronization loops by preferring servers with a lower stratum.

5.1.4.2 How are Synchronization Loops avoided?

In a synchonization loop, the time derived from one source along a specific path of servers is used as reference time again within such a path. This may cause an excessive accumulation of errors that is to be avoided. Therefore NTP uses different means to accomplish that:

-

The Internet address of a time source is used as reference identifier to avoid duplicates. The reference identifier is limited to 32 bits.

-

The stratum is used to form an acyclic synchronization network.

More precisely, according to Professor David L. Mills, the algorithm finds a shortest path spanning tree with metric based on synchronization distance dominated by hop count. The reference identifier provides additional information to avoid neighbor loops under conditions where the topology is changing rapidly. Looping is a well known problem for routing algorithms. See any textbook on computer network routing algorithms, such as Data Networks by Bertsekas and Gallagher.

In IPv6 the reference ID field is a timestamp that can be used for the same purpose.

5.1.5 Tuning

5.1.5.1. What is the allowed range for minpoll and maxpoll?

The default polling value after restart of NTP is the value specified by minpoll. The default values for minpoll and maxpoll are 6 (64 seconds) and 10 (1024 seconds) respectively.

For NTPv4 the smallest and largest allowable polling values are 4 (16 seconds) and 17 (1.5 days) respectively. These values come from the include file ntp.h. The revised kernel discipline automatically switches to FLL mode if the update interval is longer than 2048 seconds. Below 256 seconds PLL mode is used, and in between these limits the mode can be selected using the STA_FLL bit.

5.1.5.2 What is the best polling Interval?

There is none. Short polling intervals update the parameters frequently and are sensitive to jitter and random errors. Long intervals may require larger corrections with significant errors between the updates. However, there seems to be an optimum between those two. For common operating system clocks this value happens to be close to the default maximum polling time, 1024s. See also Q: 5.1.3.1.

5.1.6 Operating System Clock Interface

5.1.6.1 How will NTP discipline my Clock?

In order to keep the right time, ntpd must make adjustments to the system clock. Different operating systems provide different means, but the most popular ones are listed below.

Basically there are four mechanisms (system calls) an NTP implementation can use to discipline the system clock:

-

settimeofday(2) to step (set) the time. This method is used if the time if off by more than 128ms.

-

adjtime(2) to slew (gradually change) the time. Slewing the time means to change the virtual frequency of the software clock to make the clock go faster or slower until the requested correction is achieved. Slewing the clock for a larger amount of time may require some time. For example standard Linux adjusts the time with a rate of 0.5ms per second.

-

ntp_adjtime(2) to control several parameters of the software clock, also known as kernel discipline. These parameters can:

- Adjust the offset of the software clock, possibly correcting the virtual frequency as well.

- Adjust the virtual frequency of the software clock directly.

- Enable or disable PPS event processing.

- Control processing of leap seconds.

- Read and set some related characteristic values of the clock.

-

hardpps() is a function that is only called from an interrupt service routine inside the operating system. If enabled, hardpps() will update the frequency and offset correction of the kernel clock in response to an external signal (see also Section 6.2.4).