5.2. The Kernel Discipline

Last update: April 3, 2024 16:42 UTC (f170361b7)

In addition to the NTP protocol specification, there exists a description for a kernel clock model (RFC 1589) that is discussed here.

5.2.1 Basic Functionality

5.2.1.1 What is special about the Kernel Clock?

5.2.1.2 Does my Operating System have the Kernel Discipline?

5.2.1.3 How can I verify the Kernel Discipline?

5.2.2 Monitoring

5.2.3 PPS Processing

5.2.3.1 What is PPS Processing?

5.2.3.2 How is PPS Processing related to the Kernel Discipline?

5.2.3.3 What does hardpps() do?

5.2.1 Basic Functionality

5.2.1.1 What is special about the Kernel Clock?

NTP keeps precision time by applying small adjustments to system clock periodically. However, some clock implementations do not allow small corrections to be applied to the system clock, and there is no standard interface to monitor the system clock’s quality.

RFC 1589 defines a clock model with the following features :

- Two new system calls to query and control the clock:

ntp_gettime() and ntp_adjtime().

- The clock keeps time with a precision of one microsecond. The nanokernel keeps time using even fractional nanoseconds. In real life operating systems there are clocks that are much worse.

- Time can be corrected in quantities of one microsecond, or even fractional microseconds using the nanokernel, and repetitive corrections accumulate. The UNIX system call

adjtime() does not accumulate successive corrections.

- The clock model maintains additional parameters that can be queried or controlled. Among these are:

- A clock synchronization status that shows the state of the clock machinery (

TIME_OK).

- Several clock control and status bits that control and show the state of the machinery (

STA_PLL). This includes automatic handling of announced leap seconds.

- Correction values for clock offset and frequency that are automatically applied.

- Other control and monitoring values like precision, estimated error, and frequency tolerance.

- Corrections to the clock can be automatically maintained and applied.

Applying corrections automatically within the operating system kernel no longer requires periodic corrections through an application program.

5.2.1.2 Does my Operating System have the Kernel Discipline?

If you can find an include file named timex.h that contains a structure named timex and constants like STA_PLL and STA_UNSYNC, you probably have the kernel discipline implemented. To make sure, try using the ntp_gettime() system call.

5.2.1.3 How can I verify the Kernel Discipline?

The following guidelines were presented by Professor David L. Mills:

Feedback loops and in particular phase-lock loops and I go way, way back since the first time I built one as part of a frequency synthesizer project as a grad student in 1959. All the theory I could dredge up then convinced me they were evil, non-linear things and tamed only by experiment, breadboard and cut-and-try. Not so now, of course, but the cut-and-try still lives on. The essential lessons I learned back then and have forgotten and relearned every ten years or so are:

- Carefully calibrate the frequency to the control voltage and never forget it.

- Don’t try to improve performance by cranking up the gain beyond the phase crossover.

- Keep the loop delay much smaller than the time constant.

- For the first couple of decade re-learns, the critters were analog and with short time constants so I could watch it with a scope. The last couple of re-learns were digital with time constants of days. So, another lesson:

There is nothing in an analog loop that can’t be done in a digital loop except debug it with a pair of headphones and a good test oscillator. Yes, I did say headphones.

So, this nonsense leads me to a couple of simple experiments:

- First, open the loop (

kill ntpd). Using ntptime, zero the frequency and offset. Measure the frequency offset, which could take a day.

- Then, do the same thing with a known offset via

ntptime of say 50 PPM. You now have really and truly calibrated the VFO gain.

- Next, close the loop after forcing the local clock maybe 100 ms offset. Watch the offset-time characteristic. Make sure it crosses zero in about 3000 s and overshoots about 5 percent. That with a time constant of 6 in the current nanokernel.

In very simple words, step 1 means that you measure the error of your clock without any correction. You should see a linear increase for the offset. Step 2 says you should then try a correction with a fixed offset. Finally, step 3 applies corrections using varying frequency corrections.

5.2.2 Monitoring

Most of the values are described in Q: 6.2.4.2.1. The remaining values of interest are:

- time

- The current time.

- maxerror

- The maximum error (set by an application program, increases automatically).

- esterror

- The estimated error (set by an application program like

ntpd).

- offset

- The additional remaining correction to the system clock.

- freq

- The automatic periodic correction to the system clock. Positive values make the clock go faster while negative values slow it down.

- constant

- Stiffness of the control loop. This value controls how a correction to the system clock is weighted. Large values cause only small corrections to be made.

- status

- The set of control bits in effect. Some bits can only be read, while others can be also set by a privileged application. The most important bits are:

| Bit |

Description |

STA_PLL |

The PLL (Phase Locked Loop) is enabled. Automatic corrections are applied only if this flag is set. |

STA_FLL |

The FLL (Frequency Locked Loop) is enabled. This flag is set when the time offset is not believed to be good. Usually this is the case for long sampling intervals or after a bad sample has been detected by xntpd. |

STA_UNSYNC |

The system time is not synchronized. This flag is usually controlled by an application program, but the operating system may also set it. |

STA_FREQHOLD |

This flag disables updates to the freq component. The flag is usually set during initial synchronization. |

5.2.3 PPS Processing

5.2.3.1 What is PPS Processing?

During normal time synchronization, the server time stamps are compared about every 20 minutes to compute the required corrections for frequency and offset. With PPS processing, a similar thing is done every second. Therefore it’s just time synchronization on a smaller scale. The idea is to keep the system clock tightly coupled with the external reference clock providing the PPS signal.

PPS processing can be done in application programs, but it makes much more sense when done in the operating system kernel. When polling a time source every 20 minutes, an offset of 5ms is rather small, but when polling a signal every second, an offset of 5ms is very high. Therefore a high accuracy is required for PPS processing. Application programs usually can’t fulfil these demands.

The kernel clock model includes algorithms to discipline the clock through an external pulse, the PPS. The additional requirements consist of two mechanisms: capturing an external event with high accuracy, and applying that event to the clock model. The first is solved using the PPS API, while the second is implemented mostly in a routine named hardpps() which is called every time when an external PPS event has been detected.

5.2.3.3 What does hardpps() do?

hardpps() is called with two parameters, the absolute time of the event, and the time relative to the last pulse. Both times are measured by the system clock.

The first value is used to minimize the difference between the system clock’s start of a second and the external event, while the second value is used to minimize the difference in clock frequency. Normally hardpps() just monitors (STA_PPSSIGNAL, PPS frequency, stability and jitter) the external events, but does not apply corrections to the system clock.

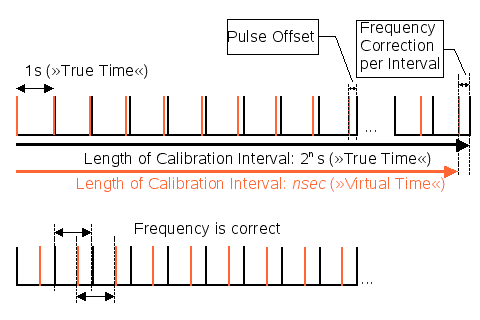

Figure 5.2a: PPS Synchronization

hardpps() can minimize the differences of both frequency and offset between the system clock and an external reference.

Flag STA_PPSFREQ enables periodic updates to the clock’s frequency correction. Stable clocks require only small and infrequent updates while bad clocks require frequent and large updates. The value passed as parameter is reduced to be a small value around zero, and then it is added to an accumulated value. After a specific amount of values has been added (at the end of a calibration interval), the total amount is divided by the length of the calibration interval, giving a new frequency correction.

When flag STA_PPSTIME is set, the start of a second is moved towards the PPS event, reducing the needed offset correction. The time offset given as argument to the routine will be put into a three-stage median filter to reduce spikes and to compute the jitter. Then an averaged value is applied as offset correction.

In addition to these direct manipulations, hardpps() also detects, signals, and filters various error conditions. The length of the calibration interval is also adjusted automatically. As the limit for a bad calibration is ridiculously high (about 500 PPM per calibration), the calibration interval normally is always at its configured maximum.